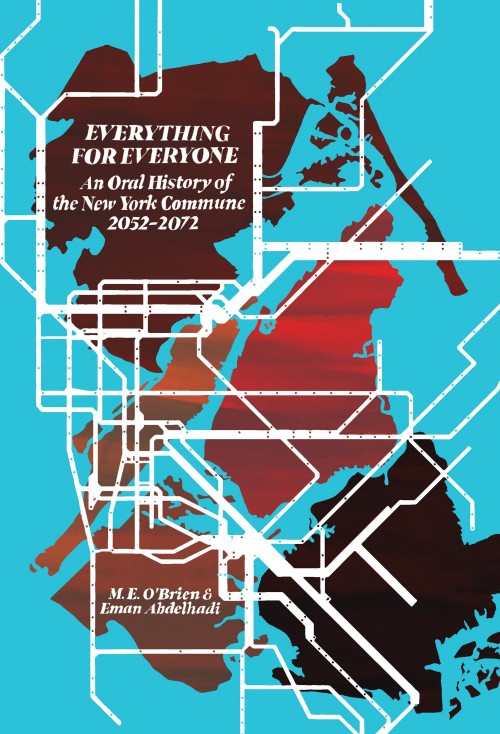

Everything for Everyone: An Oral History of the New York Commune 2052-2072

Copyright 2022, Common Notions Press

Climate Change, Fiction

“As elders, we remember a time when you had to constantly keep track of how much money you had in the bank. This amount determined whether—as one of our narrators put it-“you could afford to get sick,” whether you could keep your housing, and sometimes, even whether you could afford food. When you were hungry, you could not just wander down to your commune’s pantry and grab a snack. When you were ill, you could not just visit your care clinic and present your ailments. Even clothing and shoes had a cost! You were constantly asked to weigh the costs of your needs against each other. Nowadays, this feels like barbaric dystopia to the youth of our present and a distant, unpleasant memory to our elders.” [p9]

“John: Everything you could imagine. How to distribute food, how to keep water running, how to defend against the pigs, what to do about the holdouts, who should have guns, military strategy, every. thing. Like we were discussing how to do everything necessary that had once been done by the stores, the jobs, the entire government, and putting everything they did on the agenda to actually sort it out, what we were fighting for and how we were going to get there. Like, I facilitated a six-hour meeting about how to deal with child abuse allegations in the communes. At this point there were communes of some sort in every borough, and it had completely broken open people’s ideas of family. And no one liked the old child protective services system, they had done so much harm. So, we were arguing about what could be done, what should be done, if someone thought a kid was being abused. All of life was up for debate in a way. So, we would meet all day. Then every night there’d be one general assembly where all the various groups would report on their deci-sions, and it would get argued about. After that everyone would go back to their factions and try to convince their comrades to go along with whatever they had hashed out. The first week was just trying to get people not to shoot each other. It was resolution tables around the clock. After that, things started to settle down. We made all the participants do shifts with cooking, cleaning, childcare, and I think that helped. All these old politicos and jacked gangsters doing dishes together, I think it helped settle people, helped make people listen to each other a bit more. The facilitation team were fucking heroes, I’m telling you.” [p72]

“John: That’s what we called the armed defense efforts of the com-munes, but it wasn’t like the North American Liberation Front or formal armies. It wasn’t really an army at all. Basically, we decided the only way to defend the New York Commune was to arm and train nearly everybody who had given up property and power-that was the criteria— in how to use a gun. The orgs did the training, but in the third week of the Assembly we decided to form this “council of grandmothers” as we called it, like literally, really old women. Well, elder feminized people. But mostly women. They made the military decisions and decided when someone had to be disarmed. The army was just literally everyone who the grandmothers hadn’t decided to disarm.” [p73]

“Sanchez: The making of things to sell on the market. I think it’s difficult to overstate how much that shaped what it meant to be human, and how much is changing as we are free of it. People think the real problem was the state, or private ownership, or too many fascists, or culture change. And sure, all those were serious and all are connected. But it’s harder to see how the markets themselves, the dependency on work and wages and exchange, fundamentally distorts and damages what it means to be human. All these other horrors emerge from the impersonal violence of exchanging your time for work, and exchanging your work for goods, and exchanging those goods on a market, no matter if the state owns it, or a private firm, or even a co-op.” [p232]